FinTech (Financial Technology) is typically defined as innovations or technologies serving a financial purpose; it is regarded as a set of equipment, software, or algorithms at one’s disposal. Investopedia, for instance, defines FinTech as “the new technology that seeks to improve and automate the delivery and use of financial services” (Kagan, 2024).

The use cases of such technologies go above and beyond the applications carried out by the traditional financial sector, although the latter are adopting FinTech innovations to remain competitive. Wo ́jcik (2021a), when defining FinTech, acknowledges it as comprising innovative technologies, but also describes it as “an economic sector that focus[es] on the application of recently developed digital technologies to financial services” (Wo ́jcik, 2021a). The justification for FinTech being an emerging sector in itself lies in the multitude of FinTech firms around the globe, the variety in their organizational structure (private, public, non-profit), distinctions in their transaction approaches (for example, B2B and B2C), and the wide range of services they provide.

The current era of FinTech arguably catalyzed as a result of the 2008 Financial Crisis and accelerated with the Covid-19 pandemic (Wo ́jcik, 2021a; Wo ́jcik, 2021b). The proportion of the population having an account in a bank or any other type of financial institution – or having used mobile money service over the course of a year –has been rising at least since the past decade all around the world.

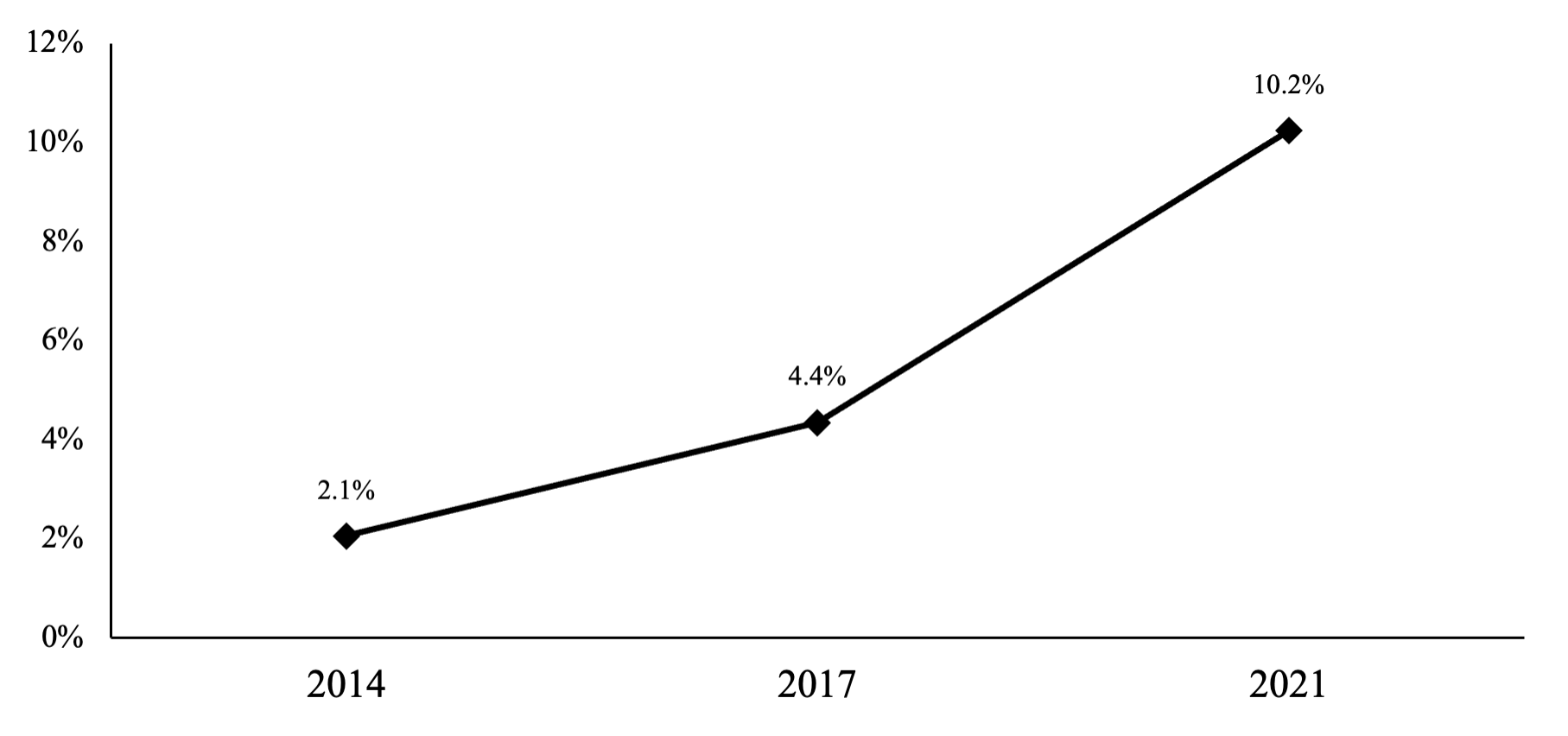

Using the Mobile Money Account (%)[1] series from the Global Findex Database, the global trend of mobile money service has clearly shot up from around 2% of the world population using it in 2014 to more than 10% availing it in 2021, as shown in Figure 1.

The emergence of FinTech, considered a set of technologies as well as an economic sector, has spurred in many the hope for poverty alleviation, a goal in line with the spirit of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This paper examines the rhetoric of FinTech as an engine of growth and poverty reduction, and explores some of the opportunities and challenges associated with it.

FinTech, Financial Inclusion & Poverty Alleviation

Perhaps the most impactful economic outcome of the FinTech revolution in recent years is financial inclusion. Financial inclusion – or the efforts to expand the accessibility and quality of financial products and services to include all populations of an economy – is viewed as an eminent “enabler” of many of the Sustainable Development Goals, including “eradicating poverty” (UNCDF, n.d.).

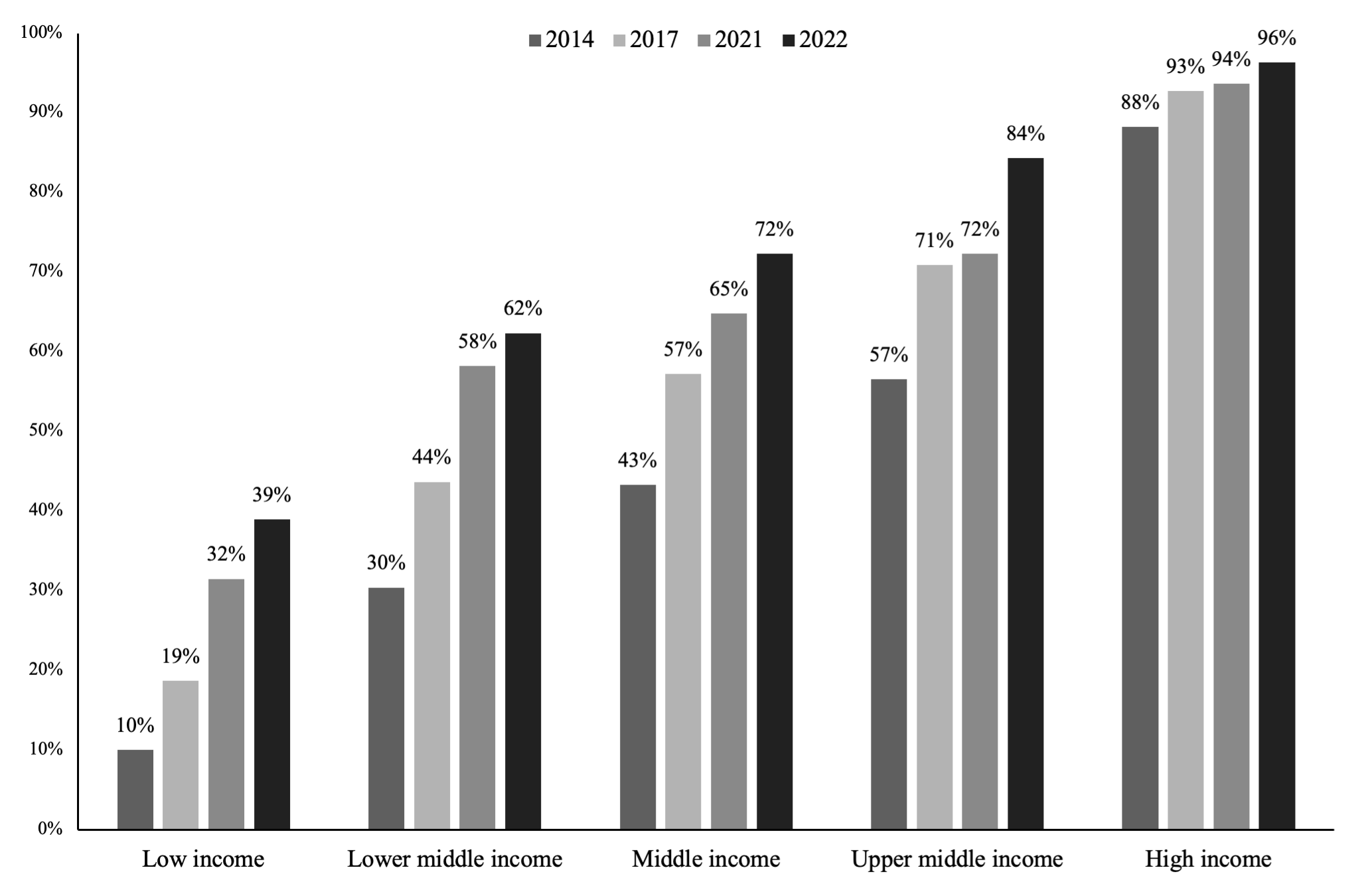

Using the Account (%) indicator[2] from the Global Findex Database, we plot (in Figure 2) the trend of financial inclusion from 2014 through 2022 for countries classified according to their income level. There is an observable positive correlation between the proportion of the population aged 15 or above that are financially included and the income level of the economy; high-income countries see the majority of their population having a financial account or using mobile money, whereas the proportion lowers down as we move towards low-income countries. Hence, graphically, there appears to be a direct positive correlation between financial inclusion (boosted by the emergence of FinTech) and economic development.

Many studies find that the adoption of FinTech in economies reduces poverty and contributes to development. Quresh et al. (2023) discussed the potential of FinTech to economically empower underserved people and the need for collaboration between involved institutions and agents to materialize the benefits of financial inclusion. Suri and Jack (2016) estimated the impact of M-Pesa—a particular mobile money system in Kenya—on individuals’ consumption levels. Their study found it “lifted 194,000 households, or 2% of Kenyan households, out of poverty.”

Ye et al. (2022) performed an empirical analysis of 31 provinces of China from 2011 through 2020. They found that digital financial technology, by extending financial inclusion to marginalized communities, “effectively reduces poverty in every province.” Appiah-Otoo and Song (2021) also found similar results regarding a positive impact of FinTech on economic growth and a negative impact on poverty in China.

For Pakistan, Tasos et al. (2020) evaluated the data of 300 households in the district of Sargodha to quantify the impact of microfinance on poverty. The results of their logistic regression showed a decline in the poverty rate from 42.7% to 29.3% owing to the availability of microfinancing to the poor. Moreover, in their sample, the authors found a negative correlation between poverty and the “duration of microfinance.”

Chhorn (2021) conducted a panel analysis on eight Southeast Asian countries for the period 1990 through 2017 to measure the impact of financial development on poverty and human development. The author utilized three indicators for financial development, namely, broad money, domestic credit, and mobile money. Their Two-Stage Least-Squares (2SLS) regression results showed that broad money and domestic credit significantly reduce poverty and promote human development, particularly in “less developed and less democratic countries” – while mobile money contributes to human development in all countries, but is not statistically related to poverty.

These results, highlighting the positive association between FinTech development and poverty reduction or economic growth, are not without criticism and reproval. Bateman et al. (2019), for example, critically highlighted the shortcomings in the methodology and approach underpinning the seminal study of Suri and Jack (2016).

Moreover, they highlighted the issue of overindebtedness in the Global South, stimulated further by the advancement of credit accessibility. Their critical appraisal concludes by describing FinTech as an innovation that “enriches elites at the expense of the poor, while also shifting risks to the poor themselves, ultimately ensuring that it is the poor that will be the ones most devastated by a future financial collapse.”

Opportunities & Challenges of FinTech

The emergence of FinTech presents a range of opportunities and challenges to economies. On one hand, improvement in digital financial technologies is argued to improve user experience and convenience in consuming financial products and services, expand reach to (real) markets, contribute efficiency in conducting transactions, and introduce opportunities for cost-effectiveness and security in institutional operations.

On the other hand, the challenges associated with this sector include regulatory issues, cybersecurity, data privacy and survaillance risks, demand for financial literacy, (digital) infrastructure requirements, and rising debt dependence.

There is also the challenge of managing the FinTech revolution equitably, as inequitable accessibility in technologically disadvantaged and economically underprivileged regions would defeat the purpose of economic development and poverty alleviation.

Friedline et al. (2020), though admitting the likely positive impact of FinTech on economic development, advanced the argument of “digital redlining” affecting financial inclusion in marginalized communities (based on income and racial classification). Their analysis of the United States reveals that rural communities that are poor and that are of color “have limited access to high-speed internet connections required for fintech.” Not only might this impede the full-scale realization of FinTect positive effects on the economy as a whole, but also “amplify marginalization.”

FinTech, understood as a set of technologies as well as an economic sector, becomes a specific topic of interest in the study of economics. Beyond the professional avenues and lifestyle conveniences offered by the technological resourcefulness of FinTech, one might be interested in exploring the interconnectedness and impacts of these inventions on firm performance, labor market, and politico-economic relations.

Moreover, as a sector in the macro-economy, FinTech would inevitably demand public policies that oversee its regulation, define its role in the (existing) financial and technology sector, and ensure that the general direction of this budding sector aligns with the larger economic goals of employment, price stability, and economic equity.

One of the financial sector’s most important functions is intermediation. In an economic sense, financial institutions offer liaison services between lenders (those who have surplus funds) and borrowers (who require funds). The financial sector performs this function at a large scale, covering the economy as a whole. The intermediary services of financial institutions lie in the middle of all (recorded) financial transactions.

The rise of FinTech presented a possibility beyond the well-established concept of intermediation, and so came the promise of disintermediation. Decentralized Finance (DeFi), for instance, is an emerging field of Web3 technologies that challenges “to remove third parties and centralized institutions from financial transactions” (Sharma, 2024). With the emergence of FinTech, the supposed disintermediation and “disruption” of how financial transactions are conducted has implications for consumerism, the traditional financial sector, and the real economy.

The analysis of Chen et al. (2019) [as cited in Wo ́jcik, 2021b], for example, found that FinTech expands the overall “pool of potential profits in the financial sector.” Partially explaining disintermediation and enlargement of the financial sector’s pie, unbundling describes the distribution of services under the preview of the financial and technology sector across a multitude of specialized firms.

Geographers and other analysts, on the other hand, argue that FinTech institutions contribute to the “process of re-intermediation” (Wo ́jcik, 2021b). They claim that the process of unbundling and expansion (into the traditional financial sector) may be followed once again by the centralization of services by “re-bundling, driven by economies of scale, scope, and networks” (Wo ́jcik, 2021b). Hence, the FinTech sector, some contend, plays into the power struggle for profit and control, and may possibly drive centralization at industrial or state level.

Conclusion

To summarize, FinTech holds much promise for economic development and poverty alleviation. However, its potential benefits come in conjunction with different regulatory, socio-economic, and political challenges.

In the public policy sphere, continuous innovations in digital financial technologies present governments and central banks with the issues of defining and redefining, dynamically, consumers’ rights and regulations related to institutional behavior. In the socio-economic domain, FinTech proffers new avenues for promoting economic growth, but at the same time, demands active management and investment (especially in disadvantaged areas) for fruitful and equitable realization of its potential. In the political realm, FinTech breeds hope in some and despair in others for its multifarious implications on the evolution of democracy, capitalism, and state-market power dynamics.

Notes

[1] Global Findex Glossary defines the indicator as “the percentage of respondents [aged 15 or above] who report personally using a mobile money service in the past year.” [2] Global Findex Glossary defines it as “the percentage of respondents [aged 15 or above] who report having an account (by themselves or together with someone else) at a bank or another type of financial institution or report personally using a mobile money service in the past year.”References

Appiah-Otoo, I., & Song, N. (2021). The impact of fintech on poverty reduction: Evidence from China. Sustainability, 13(9), 5225.

Bateman, M., Duvendack, M., & Loubere, N. (2019). Is fin-tech the new panacea for poverty alleviation and local development? Contesting Suri and Jack’s M-Pesa findings published in Science. Review of African Political Economy, 46(161), 480-495.

Chen, M. A., Wu, Q., & Yang, B. (2019). How valuable is FinTech innovation? The Review of Financial Studies, 32(5), 2062-2106.

Chhorn, D. (2021). Financial development, poverty, and human development in the Fintech age: a regional analysis of the Southeast Asian states [version 1; peer review: 2 approved with reservations]. Open Research Europe, 1, 118.

Friedline, T., Naraharisetti, S., & Weaver, A. (2020). Digital redlining: Poor rural communities’ access to fintech and implications for financial inclusion. Journal of Poverty, 24(5-6), 517-541.

Kagan, J. (2024). Financial technology (Fintech): Its uses and impact on our lives. Investopedia.

Quresh, M., Ismail, M., Khan, M., & Gill, M. A. (2023). The impact of fintech on financial inclusion: Opportunities, challenges, and future perspectives. PalArch’s Journal of Archaeology of Egypt/Egyptology, 20(2), 1210-1229.

Sharma, R. (2024). What is Decentralized Finance (DeFi) and how does it work? Investopedia.

Suri, T., & Jack, W. (2016). The long-run poverty and gender impacts of mobile money. Science, 354(6317), 1288-1292.

Tasos, S., Amjad, M. I., Awan, M. S., & Waqas, M. (2020). Poverty alleviation and microfinance for the economy of Pakistan: A case study of Khushhali Bank in Sargodha. Economies, 8(3), 63.

UNCDF. (n.d.). Financial inclusion and the SDGs. United Nations Capital Development Fund.

Wojcik, D. (2021a). Financial geography I: Exploring FinTech–maps and concepts. Progress in Human Geography, 45(3), 566-576.

Wojcik, D. (2021b). Financial geography II: The impacts of FinTech–Financial sector and centres, regulation and stability, inclusion and governance. Progress in Human Geography, 45(4), 878-889.

Ye, Y., Chen, S., & Li, C. (2022). Financial technology as a driver of poverty alleviation in China: Evidence from an innovative regression approach. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 7(1), 100164.